Dplyr::cummean - Cumulative mean cummin - Cumulative min cumprod - Cumulative prod cumsum - Cumulative sum RANKINGS dplyr::cumedist - Proportion of all values dplyr::denserank - rank with ties = min, no gaps dplyr::minrank - rank with ties = min dplyr::ntile - bins into n bins dplyr::percentrank - minrank scaled to 0,1. Cheatsheets is a collection of bioinformatics cheat sheets we've written. Email coding4medicine with suggestions and changes. Theme credit - rstacruz.rstacruz.

- R Data Cleaning Cheat Sheet

- R Studio Dplyr Cheat Sheet

- Tibble Cheat Sheet

- Tidyr Cheat Sheet

- R Dplyr Cheat Sheet Deutsch

In a previous post, I described how I was captivated by the virtual landscape imagined by the RStudio education team while looking for resources on the RStudio website. In this post, I’ll take a look atCheatsheets another amazing resource hiding in plain sight.

Apparently, some time ago when I wasn’t paying much attention, cheat sheets evolved from the home made study notes of students with highly refined visual cognitive skills, but a relatively poor grasp of algebra or history or whatever to an essential software learning tool. I don’t know how this happened in general, but master cheat sheet artist Garrett Grolemund has passed along some of the lore of the cheat sheet at RStudio. Garrett writes:

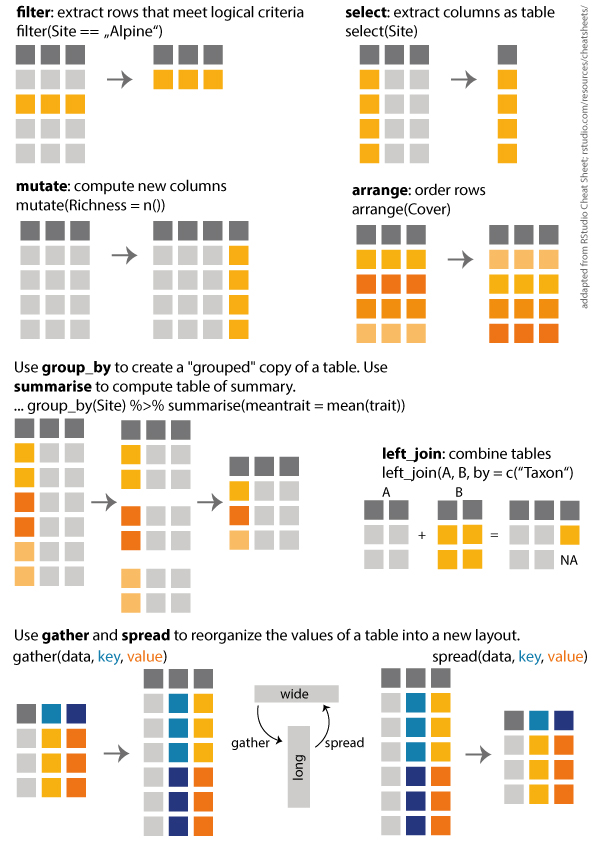

R for Data Science; Data Wrangling Cheat sheet; Introduction to dplyr; Data wrangling with R and RStudio; Key Points. Use the dplyr package to manipulate dataframes. Use select to choose variables from a dataframe. Use filter to choose data based on values. Use groupby and summarize to work with subsets of data. Use mutate to create. The Data Transformation cheat sheet is a classic example of a straightforward mnemonic tool. It is likely that even someone who just beginning to work with dplyr will immediately grok that it organizes functions that manipulate tidy data. The cognitive load then is to remember how functions are grouped by task. Dplyr provides a grammar for manipulating tables in R. This cheat sheet will guide you through the grammar, reminding you how to select, filter, arrange, mutate.

One day I put two and two together and realized that our Winston Chang, who I had known for a couple of years, was the same “W Chang” that made the LaTex cheatsheet that I’d used throughout grad school. It inspired me to do something similarly useful, so I tried my hand at making a cheatsheet for Winston and Joe’s Shiny package. The Shiny cheatsheet ended up being the first of many. A funny thing about the first cheatsheet is that I was working next to Hadley at a co-working space when I made it. In the time it took me to put together the cheatsheet, he wrote the entire first version of the tidyr package from scratch.

It is now hard to imagine getting by without cheat sheets. It seems as if they are becoming expected adjunct to the documentation. But, as Garret explains in the README for the cheat sheets GitHub repository, they are not documentation!

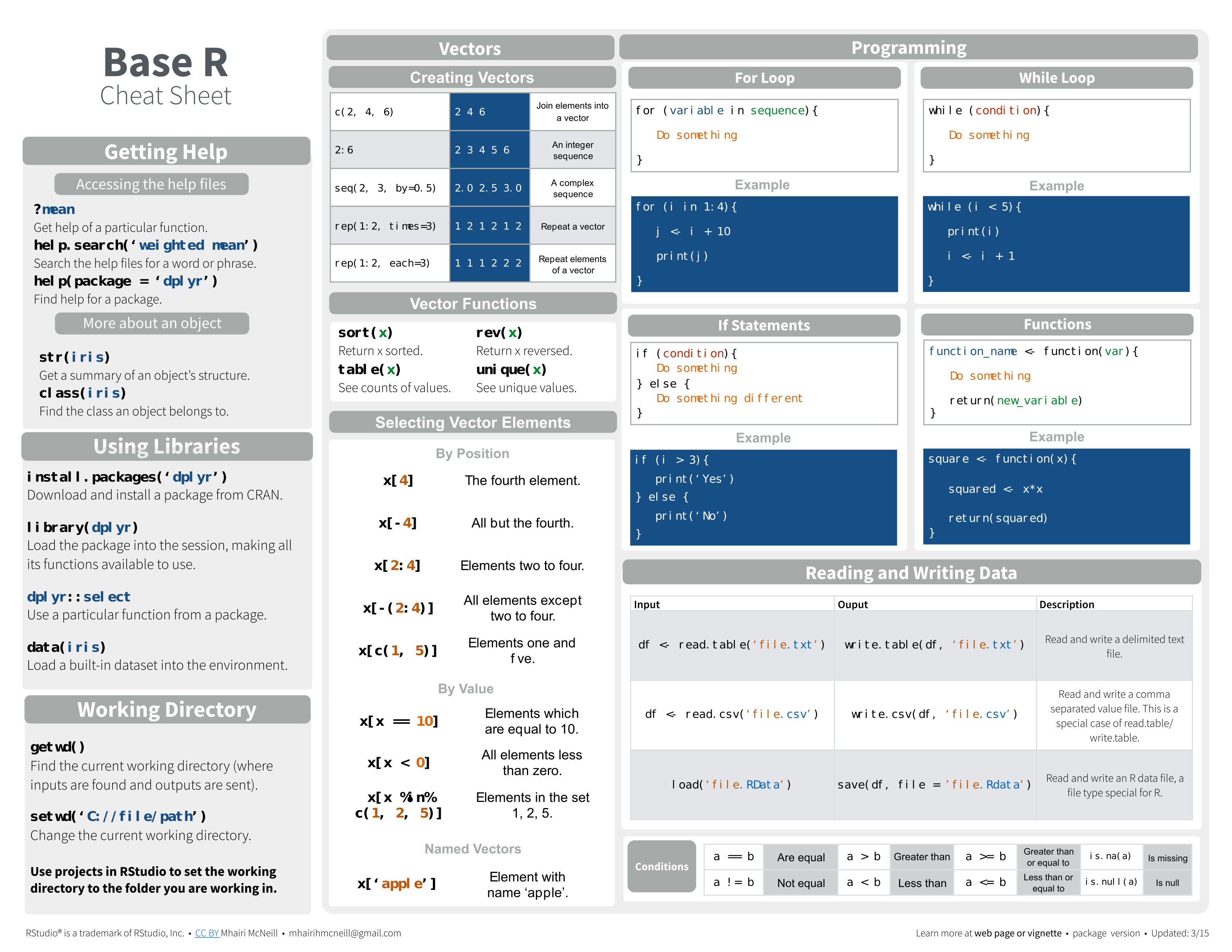

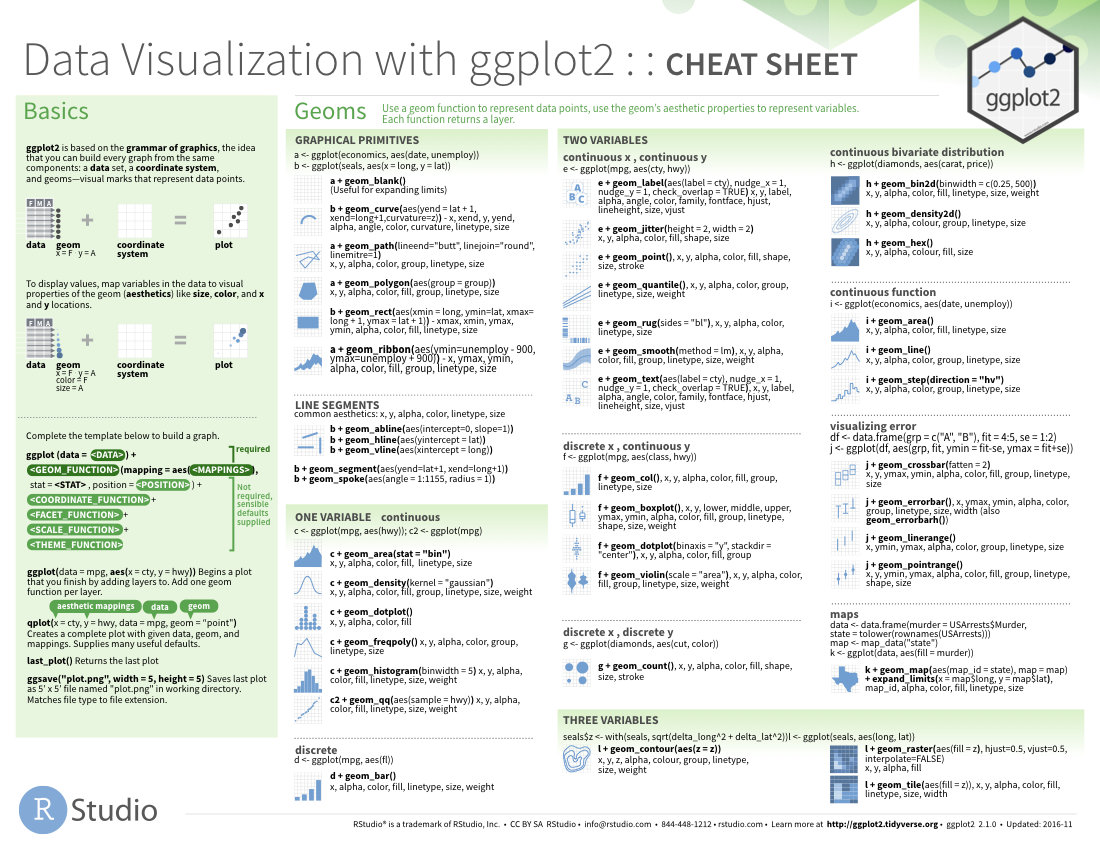

RStudio cheat sheets are not meant to be text or documentation! They are scannable visual aids that use layout and visual mnemonics to help people zoom to the functions they need. … Cheat sheets fall squarely on the human-facing side of software design.

Cheat sheets live in the space where human factors engineering gets a boost from artistic design. If R packages were airplanes then pilots would want cheat sheets to help them master the controls.

R Data Cleaning Cheat Sheet

The RStudio site contains sixteen RStudio produced cheat sheets and nearly forty contributed efforts, some of which are displayed in the graphic above. The Data Transformation cheat sheet is a classic example of a straightforward mnemonic tool.It is likely that even someone who just beginning to work with dplyr will immediately grok that it organizes functions that manipulate tidy data. The cognitive load then is to remember how functions are grouped by task. The cheat sheet offers a canonical set of classes: “manipulate cases”, “manipulate variables” etc. to facilitate the process. Users that work with dplyr on a regular basis will probably just need to glance at the cheat sheet after a relatively short time.

The Shiny cheat sheet is little more ambitious. It works on multiple levels and goes beyond categories to also suggest process and workflow.

The Apply functions cheat sheet takes on an even more difficult task. For most of us, internally visualizing multi-level data structures is difficult enough, imaging how data elements flow under transformations is a serious cognitive load. I for one, really appreciate the help.

Cheat sheets are immensely popular. And even in this ebook age where nearly everything you can look at is online, and conference attending digital natives travel light, the cheat sheets as artifacts retain considerable appeal. Not only are they useful tools and geek art (Take a look at cartography) for decorating a workplace, my guess is that they are perceived as runes of power enabling the cognoscenti to grasp essential knowledge and project it in the world.

When in-person conferences resume again, I fully expect the heavy paper copies to disappear soon after we put them out at the RStudio booth.

- Authors: Ahmed Hasan

- Research field: Genomics

- Lesson topic: Data wrangling with dplyr and magrittr

- Lesson content URL: https://github.com/UofTCoders/studyGroup/tree/gh-pages/lessons/r/dplyrmagrittr

- Lesson video stream: coming soon!

Why dplyr and magrittr?

dplyr is a package for data wrangling and manipulation developed primarily by Hadley Wickham as part of his ‘tidyverse’ group of packages. It provides a powerful suite of functions that operate specifically on data frame objects, allowing for easy subsetting, filtering, sampling, summarising, and more.

The overall philosophy binding dplyr together is rather simple - save for a select few exceptions, nearly every function in the package follows the convention of taking in a data frame as input and returning a modified data frame as output. Coupled with the pipe operator from the magrittr package, chaining dplyr functions together makes data frame manipulation an absolute breeze.

Meet the pipe

The R pipe, or %>% (Ctrl/Cmd + Shift + M in RStudio) initially began life outside of dplyr, finding its R beginnings in the magrittr package instead. Its creator, Stefan Milton Bache, was inspired by the pipe operator in F# (|>) in addition to its Unix shell equivalent (|).

Much like in those examples, the idea behind the magrittr pipe is also relatively simple: it essentially stands for ‘evaluate the left hand side, and feed the result as input to the function on the right hand side’. For functions that take multiple arguments, the pipe will feed it to the first one by default. Like so:

Of course, sometimes we want our LHS to be fed into a different argument that just so happens to not be the first one. In these cases, we use . to tell R where to send the LHS instead:

Given the dplyr concept of each function taking in a data frame and returning a modified version, it made a lot of sense to integrate the pipe into the dplyr workflow. This way, a given data frame would be ‘piped’ through a series of functions one after the other in order to obtain a specific desired output.

To summarise:

Tidy data

One final thing to note before we delve into dplyr itself is the concept of tidy data. This basically describes a data set where each column is a variable or feature of the data, and every row is a single observation. Fisher and Anderson’s iris, which we’ll be using in today’s lesson, is a good example of a tidy dataset.

The iris dataset gives measurements of sepal length/width and petal length/width for 50 flower samples from each of Iris setosa, Iris versicolor, and Iris virginica. Notice how each row corresponds to measurements from a single flower sample, and each column represents a specific feature of that flower.

dplyr is optimized for use with tidy data. However, real world data are rarely in a tidy format from the get-go. For this reason, Hadley and co. have also developed the tidyr package, which provides useful functions for reshaping data. We won’t be covering tidyr in today’s lesson, but a wealth of tutorials are available online.

Alright, let’s dive right into dplyr!

filter - subsetting rows

filter is the first dplyr verb we’ll be looking at. At its core, and much like all dplyr functions, filter will take an input data frame as its first argument. Following that, we can define a set of conditions that we want to filter the rows of our data frame by.

To begin with, let’s look at all the flowers that have a sepal length greater than or equal to 7.0 cm.

R Studio Dplyr Cheat Sheet

We can simply tack on any further conditions we might want to filter by as separate arguments:

select - subsetting columns

select operates in a similar fashion to filter, but allows for subsetting columns instead. Since select is primarily given column names (which can be thought of as text strings) for input, it also allows for easy globbing of multiple columns at once.

A quick aside - we are also going to convert iris to a tibble from this point onwards. Tibbles are another feature of dplyr; they’re essentially data frame objects with a number of under-the-hood improvements, but those are somewhat beyond the scope of this lesson. What’s relevant to us here is that they prevent R from printing out the entire data frame when it’s called, and are also previewed in an informative format that tells us about the object types stored within each data frame column and more. (More details here if you’re interested.)

We can select multiple columns by simply providing their names as further arguments. dplyr also allows use of the : operator for consecutive columns.

The - operator can be used to exclude a column:

Finally, select features the helper functions contains, starts_with, and ends_with for globbing column names. Note that while we generally treat column names as objects in the body of dplyr functions, these helper functions require strings as input.

Here comes the pipe

But what if we want to select certain columns, and then filter the resultant rows by a certain condition? (Or vice versa)

We could certainly nest functions, like so:

But this is messy enough as is, and that’s just with a single instance of nesting. Imagine we had three or four nested functions! We’d fast approach having more parentheses than actual code.

An alternative is using intermediate objects:

But that can be a drain on memory if we’re working with large amounts of data; not to mention that the number of intermediates would only grow as our analysis goes on, increasingly cluttering our workspace.

However, recall that every dplyr function both takes in a data frame object as its first argument, and returns one as output. With this being the case, the pipe allows us to easily chain dplyr functions together.

Notice how that code is both easy to conceptualize and understand after the fact, and that neither of the dplyr functions have the data frame actually listed as part of their arguments. The overall code block effectively reads like:

In using the pipe with dplyr functions, we can write up simple ‘recipes’ that manipulate data frame objects in a quick and straightforward manner.

Of course, there’s more to dplyr than just subsetting -

arrange - sort your data

Much like the name implies, arrange allows us to sort data. Not much to it:

Sorting in descending order is not much harder:

Finally, feeding two (or more) arguments to arrange will be interpreted as ‘sort by first column and then by second column’.

mutate - make new variables

mutate is arguably where dplyr really comes to life. So far, we’ve just been playing around with existing data, subsetting it and arranging it how we please. Which is certainly very useful! But mutate allows us to create entirely new variables (i.e. columns) in our data frame object out of operations performed on the data frame itself.

mutate employs window functions in order to do this. Unlike an aggregation function (such as mean) which takes in $n$ values and returns one value, a window function will take in $n$ elements as input and return $n$ elements as output. In the case of mutate, this means performing an operation on every single row of a data frame and returning the resultant values in a new column.

Let’s use mutate to calculate the approximate area of sepals and petals in our dataset.

We could also get the differences between sepal length and petal length for each flower:

Gone are the days of clumsy loops over data frame rows!

Of course, if we are performing some kind of complex operation that mutate is behaving strangely with, we can use rowwise to evaluate the operation one row at a time.

Finally, it is sometimes useful to drop all other columns once we’ve performed a mutate operation. Instead of having to use select after the fact to keep the columns we need, transmute is a version of mutate that only keeps the variables you create.

Notice how the Species column is also gone in the example above.

summarise - summarise your data

Where mutate is all about window functions, summarise returns us to the familiar world of aggregate functions, outputting a single value for however many values are fed as input. These should generally be quite familiar:

The important thing to note is that in using summarise, we are obtaining our summary values within a data frame structure still. Using something like mean outside of summarise would simply return a float.

group_by - group your data

Tibble Cheat Sheet

group_by is primarily a helper function itself, but it provides an immense amount of added utility to mutate and summarise. It does so by adding grouping information in an under the hood fashion. While this does not necessarily do anything explicit to the data, both summarise and mutate behave quite differently when presented with a grouped data frame.

For instance, let’s redo the summarise function we did above, but now in a grouped manner:

We can also quickly obtain the total number of records for each species:

Or the number of distinct values in a given column:

group_by also works with mutate for grouped operations. For instance, if we want to examine the ratio of each flower’s sepal length from the mean for that species, we could try something like this:

In this example, mean(Sepal.Length) is computed for each species, instead of from the entire dataset.

Finally, grouping information can be removed with the ungroup function. This is useful when performing one grouped operation and then performing a second in the same dplyr chain but off of a different column grouping.

To summarise

selectallows you to subset by columnfilterallows you to subset rows that meet one or more conditionsarrangeallows you to sort your datagroup_byallows you to group your data for grouped downstream operationsmutateallows you to compute new variables from your datasummariseallows you to apply summary functions on your data

The official Data Wrangling with R cheat sheet is a stellar reference for working with all these functions and more. Chain them together however you please using the pipe, and watch your adventures wrangling data frames become substantially more straightforward!

Tidyr Cheat Sheet

Some magrittr tricks

While we may have covered the basics of dplyr and how the pipe synergizes with it, it’s still worth going over some of the unique tricks magrittr itself offers.

The tee operator - %T>%

Another operator that derives its inspiration from the Unix shell equivalent, the tee operator will still pass on LHS to RHS, but returns LHS to stdout instead of RHS.

In the context of a dplyr chain of commands, this is especially useful when we are saving the final result of said commands back to a data frame, but also have some kind of ancillary function tacked on at the very end (i.e. plot()) that we don’t want saved to the object.

Here, the tee operator allows us to view a plot of our data, but without the output of plot ending up saved to the sepalsonly object. plot is therefore still part of our command chain, but not in an obtrusive way.

R Dplyr Cheat Sheet Deutsch

The compound assignment operator - %<>%

The compound assignment operator also comes in handy when we’re performing a series of dplyr commands on a data frame and saving the results back to it.

Where we might do:

The compound assignment operator makes for a useful bit of shorthand: